By Jobart Bartolome

Like many of the attendees of the Psycho-Spiritual Intervention (PSI) sessions, Anna (not her real name) hardly said a word on the first day.

She was reluctant to speak, especially in the big group.

Likewise, Faye (not her real name), who belonged to a previous batch, didn’t open up until the seventh and last session, despite being nudged to share in all the sessions.

This isn’t uncommon, regardless of whether their loved ones were killed in the early days of Duterte’s drug war or under the current administration.

Since face-to-face PSI sessions resumed last year, a good number of attendees were from families of victims who were killed in 2016 or 2017. And for most of them, Paghilom was where they first shared their stories.

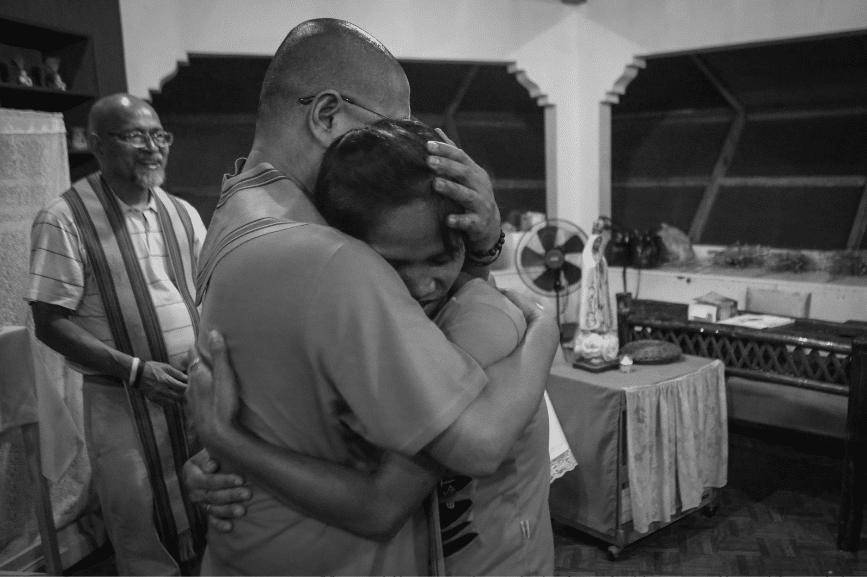

Photo credit: Raffy Lerma

We must not forget the context, and their situation before joining Paghilom.

They belong to the laylayan, the poorest of the poor.

Some of the victims were indeed drug users; while others were completely innocent.

Either way, the violent killing of their loved ones was heart-wrenching and unjust, making their lives even worse.

Having lost their breadwinners, many families don’t just struggle financially because of death and burial expenses, they also grapple with social stigma and intimidation.

Their neighbors—and sometimes even relatives—shun them and talk behind their backs.

Trust became nearly impossible; the government, its institutions, and people in general were all suspect.

But they have children and grandchildren to feed and care for, several of whom are also bullied by classmates and peers.

Many of them continue to be haunted by angry thoughts and desires to avenge the deaths of their loved ones.

Guilt plagues many of them, who often blame themselves for what had happened.

Months—and even years—would go by as they went through the different stages of grief: anger, denial, bargaining, depression, etc., without fully making sense of it all.

“Mayroong may tampo sa Diyos, bakit pinayagan na mangyari ito sa kanila?” (Some resented God, questioning why He had even allowed such a thing to happen to their family.)

We would soon discover that we were practically the first ones to ever hear them tell the stories of how their loved ones were killed.

It‘s striking that they were only able to do so because they were in a safe space.

One EJK mother shared: “Kapag may nakikinig pala, nagiging bukas ka at nakukuwento ang lahat ng nararamdaman.” [I realize that if someone is willing to listen, you are able to tell your story and how you really feel.”]

We couldn’t help but notice how their faces softened and changed as they got used to sharing their stories, especially their feelings, while we listened.

Anna, along with many others, soon began to smile as they revealed even more details.

During the culminating activity, the 3-day retreat, Anna disclosed that before attending Paghilom sessions, she refused to comb her hair, had no desire to mingle with others, and mostly, just kept to herself. Her house, she said, was always dark and dead quiet.

Taking a chance with Paghilom, she said she couldn’t believe how the experience changed her—her feelings, outlook in life, and even her posture.

It was also during the retreat that Faye began to share the back story of her hard life. Her face had also brightened up. I guess that she found a “family” she can trust.

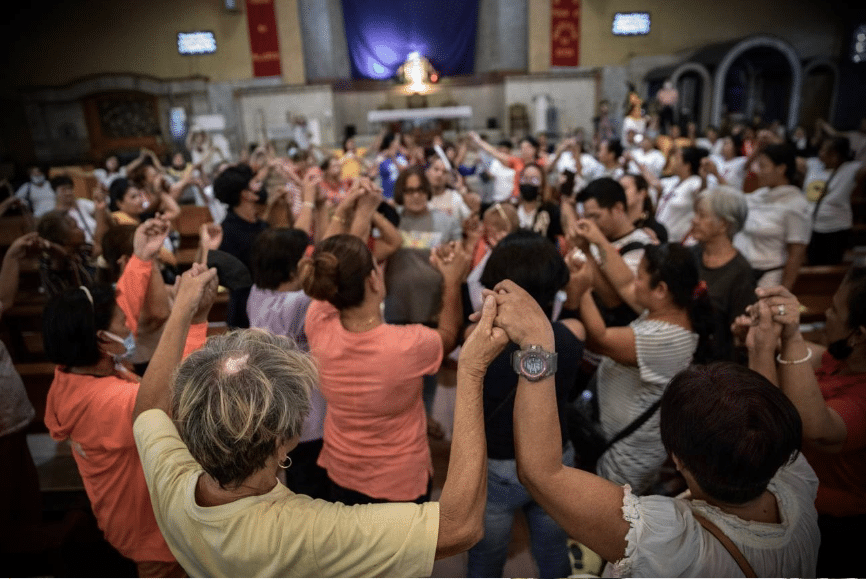

“We lost a loved one, yet gained a loving family,” as those who are active in Paghilom say.∎